Thursday's Guardian Country Diary concerns the fungus that produces these colourful symptoms on bramble leaves - bramble leaf rust, Phragmidium violaceum.

The fungus initially develops within the green leaf, causing purple patches, but when the leaf begins to die and loses its chlorophyll this vibrant 'plums and custard' colour scheme turns the leaves into some of the brightest objects in the hedgerow in early winter.

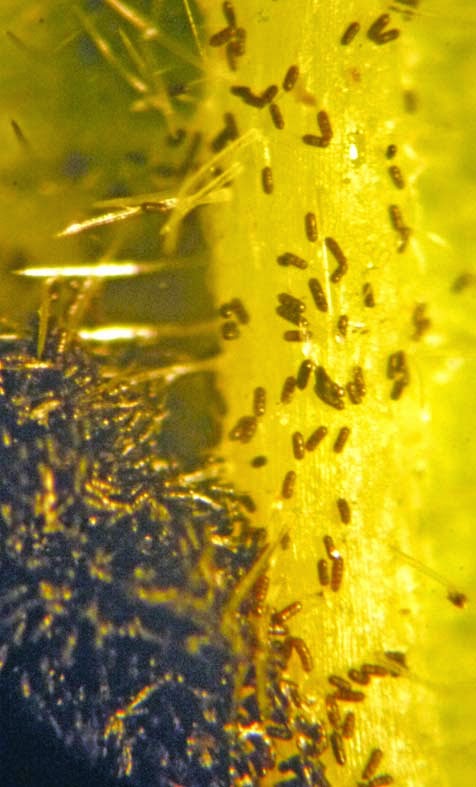

These clusters of spores erupt through the underside of the leaf as it begins to die.

The individual spores are just about visible with a camera macro lens but for a clear view you really need a microscope.

These are the individual spores viewed at about x20 with a low power stereomicroscope, and .....

.... here they are seen though a compound microscope at a magnification of around x100, showing their very distinctive club-shaped structure, with 4-5 spores on a stalk.

In Victorian times rust fungi were popular, easily accessed

subjects for amateur microscopists and in 1870 the somewhat eccentric

naturalist Mordecai Cubitt Cooke devoted a whole book, entitled Rust,

Smut, Mildew and Mould: An Introduction to the study of Microscopic Fungi, to

their study. It’s hard to imagine such a title attracting many buyers now but

in Cooke’s day, without thedistractions of television, radio and the internet,

microscopy was a very popular pastime and the book ran through four editions in

20 years.

Mordecai Cubitt Cooke

Cooke was evangelical when it came to promoting the delights

of microscopy, opening his first chapter with the confidant assertion that “everyone

who possesses a love for the marvellous, or desires a knowledge of some of the

minute mysteries of nature, has, or ought to have, a microscope.” In his

day the lady of the house would be perfectly happy for her husband to retreat

to his study for a close look at smut – or rusts, mildew and mould – in the knowledge

that he would be advancing the cause of science.

A plate from Rust, Smut, Mildew and Mould. The spore of Bramble leaf rust is illustration number 35.

![[rust1.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh3rQih89TLacN-G0aVZM484Eu8MHMx4Z9DIrBdbJZKTNl8gRjcBseWrhWR3kS6AkAAo3erdjnAOLmVQQhB_pZ-cp6TnNGRM-nISM2OQwBaE_ouQEjgmxe1kTfdVQ0VOI8TnnbaK7Wg9tq2/s640/rust1.jpg)

![[rust2.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhu7w9aRHm_TWozMhyL_62nS5YznldU4gUNMuCAK1zyEiNYNLNacTlsvlkozzqVkZF0JxZANth_iLMb4ZFIsNAFkalxS5ibgklJihjNHcGDcy3z8xICqH-KEIaWMAKiXOzASi6KKwfKTMPV/s640/rust2.jpg)